The changes in the past 50 years in the institutional structures of the rapidly rising star of the world economy – China – have been remarkable. To make sense of how the Chinese Communist Party managed to maintain its legitimacy after Mao’s death and their position as sole governing power while fundamentally transforming institutional hierarchies, I will use Margaret Archer’s morphogenetic approach. As an applied example, I have chosen China from 1976, when Mao died, until the turn of the century and the institutional stabilization of the system. I argue that Archer’s morphogenetic approach can help explain and disentangle how the economic transformations were intrinsically tied to the political survival of the Communist Party in China.

Archer’s Morphogenesis

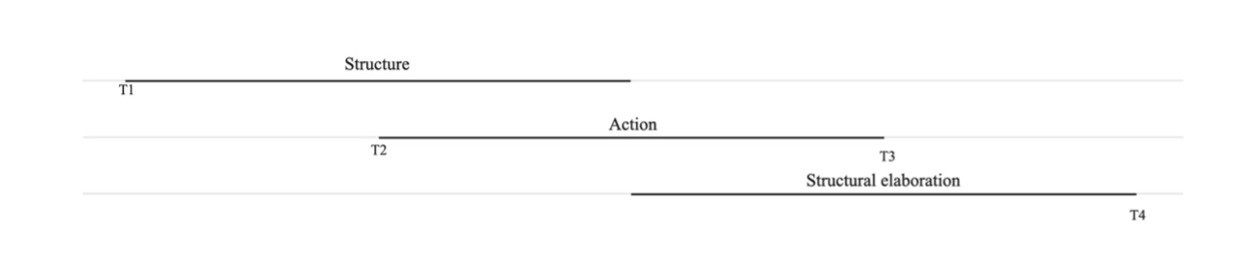

As a theory for the ontological foundations of social structures, Margaret Archer’s morphogenetic approach can be well utilized to understand the underlying transformation of, for example, the Chinese political economy (see Sommer, 2022). Archer’s is a versatile but convincing theory that overcomes the structure/agency divide, as well as the individualism/collectivism debate. Archer begins by disseminating the dichotomy between structure and agency. Morphogenesis is the fundamental process of social change, which I will occasionally call crisis in this text. It posits that structures predate and constrain the actions that cause transformation. However, this transformation in turn also elaborates and changes the initially constraining structures (1995, p.238). Thus, Archer suggests that transformation occurs in an overlapping but temporally sequential manner – see Figure 1.

Figure 1: temporally sequence of structural change, adapted from Archer, 2010, p.238

Double Morphogenesis

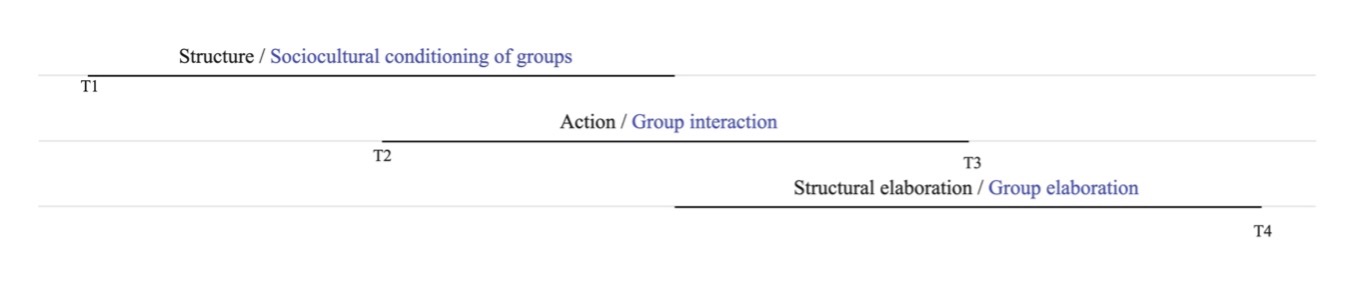

However, this is not only useful to look at the systemic outcomes of morphogenetic change, as Archer provides additional layers of transformation. She points out that during the process of change, the action or agency that causes structural change (elaboration), also changes itself. This transformation of agency is called “double morphogenesis”. This means, that throughout the process (pictured in Figure 1) the systemic outcomes are simultaneously emergent with the outcomes for agency, or in a more applied sense, in outcomes for the way social groups are formed and rearranged and interact (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: temporal sequence of change for structures and agency itself, adapted from Archer, 2010, p.238

One of the strengths of the morphogenetic approach is that it clearly recognizes the human being, the social agent, as well as the social actor as distinctive and emergent, and refuses to conflate them (Archer, 1995, p.249). This way the false dichotomy of individuals versus collectivities is dispelled. In the context of social change, it is therefore necessary to look at the transformative consequences of agency on structures, agents (the collectivities/groups) and actors. For Archer this distinction is crucial; agentsrefers to the various collectivities in society, which are defined by sharing the same life chances and thus pursue the same interest of improving or protecting said life chances. Of these, there are two types: corporate agents that are involved and can shape actions and change, whereas primary agents are also collectivities that are influenced but who cannot themselves influence because they do not have enough power (Archer, 1995, p.259).

Triple Morphogenesis

In contrast, an actor is the term for the individual, specific and emergent role a person can take on. These specific identities can be personified by humans in “particularistic” ways and are given a certain motivation to act due to their emergence and formation (or reformation) by agents – interest-driven collectivities (Archer, 1995, p. 256). Hence, people are agents first, and then with the purpose and motivation of their collectivity, the person proceeds to fill a role of an actor.

The final layer of Archer’s approach explains the creation/change of actors. Triple morphogenesis is the conditioning (but not determining) influence of agency, which thus takes place at the end of an interaction between agents, as to who will fill which (possibly new) social roles. These roles come in sets (due to their relationality) and are durable despite changes in holders. However, actors can be acted out differently by different holders (ibid. p.275-6).

Example of the double morphogenesis in China at the beginning of the crisis

In my analysis I want to situate the development of China’s political economy in the framework of the structural morphogenesis, followed by a specific example of agents and their interactions in the double morphogenesis, and finally, an example of the consequent triple morphogenesis. I want to show the explanatory value of using all three aspects of the theory and how, in an applied case, they are fundamentally interwoven. However, I will keep it simple and not differentiate between ideational and material, as Sommer (2022) does, or go into the situational logics and the reflexivity of the T3-T4 period (see Archer 1995; and Sommer 2022 for an applied case with China).

The start of the action in the morphogenesis or crisis – so T2 (see Figure 1, 2)is in 1976, when, most importantly, Mao Zedong died. The crisis was structurally conditioned by Mao’s cult of personality and unique position, which was the key. With the loss of his position as connection between party and army, as well as his cult of personality, the party that outlived him faced an issue of legitimacy and hence of political survival. This first public questioning of legitimacy manifested in the 1976 Tiananmen Square protests. In combination with Mao’s death only a short time later, these events can be considered the start of the crisis which resulted in massive changes in the economic system. Some authors, for example Boyer (2012), consider these extensive market reforms as part of a legitimacy compromise between the party with the Chinese population; the CCP offering improved material living conditions in exchange for their political monopoly. I, however, am inclined to agree with Sommer (2022; n.d.b) who argues that the “open up and reform” strategies were rather a necessity for the renewed loyalty of the army, which in exchange for major financial commitment would fully support the party.

The following is an example for the double morphogenesis, supports the latter hypothesis and is situated within the interaction period between T2 (1976) up to T3 (1993). As the first reaction to the Tiananmen protests, and briefly before his death, Mao appointed Hua Guofeng as his successor. Once Hua took power the precarity of the situation became apparent. Thus, he almost immediately had the Gang of Four arrested which maintained the momentary stability. Although Hua was officially chairman, the true power lied with Deng Xiaoping from 1978 on.

In this time period the interactions of agents are clearly distinguishable. From this moment on the corporate agents in this situation were Hua Guofeng and his “whateverist” “Little Gang of Four” who tried to uphold “whatever” Mao would have done and aimed to maintain Mao’s legacy. The other corporate agents were the rest of the party, who were yet again split into two camps; the reformers (who supported market reform) and the conservatives (who were in favor of planning). As these groups interacted, they (a) tried to maintain stability and stay in power (whateverist camp and Hua) or advance to power (rest of CCP elites) (this is the structural morphogenetic process) and (b) also simultaneously change the arrangement of the groups themselves (the double morphogenesis).

This situation is also a very clear representation of how agents and their interactions (agency) constrain the actors. The actor in question is the role of the general secretary, in this case, filled by Hua Guofeng, representing the whateverist camp aiming to maintain power. However, when in 1981 Mao’s legacy was decided by most of the party members - after the rest of Hua’s group had been purged in 1980, the resulting distancing to Mao and his policies led to Hua’s dismissal by the other agents (Sommer, n.d.a).

Examples of the triple morphogenesis at the end of the interaction period (1993)

To illustrate the triple morphogenesis, I will use the example of how Deng understood the structural origin of the legitimacy crisis and reestablished one unified core. The core is the highest powerholder; it combines both the party and the military, in the democratic centralism system predominant in China since Mao. The system works by including a variety of voices (the democratic part) with a final decision maker (the centralism part). During Mao’s more centralist rule, he was the core, supported by his personality cult – this was however lost with his death, as Hua was only general secretary of the party and was not in supreme control of the army. In the 80’s the democratic part of democratic centralism works well – as a result of the lack of a core, as both corporate agents – the reformers under Deng Xiaoping and the conservatives under Chen Yun – followed their own cores. This however, lead to inefficiencies. Additionally, in combination with a split authority over the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) with the Central Military Commission (CMC) the army had two equal authorities and was forced to choose sides. Additionally, the PLA had been underfunded and overlooked for a long time, partly due to it being deprioritized in the modernization process throughout the 80s. This lack of funding and attention on the military complex in general also heavily factored into the second Tiananmen Square tragedy in 1989 as the PLA lacked the adequate resources to deal with riots (Sommer, n.d.b).

The triple morphogenesis resulted in a key actor – the core – that represented the reformers while also (democratically) including the voices of the conservatives, considering the urban and rural areas, including both the army and the party, and making one final decision. This was implemented by Deng who in 1991/92 completed the Southern Tour to ensure the compromise between the “impoverished military and the richer coastal provinces to stabilize the Party and reinstate its core” (Sommer, n.d.b, p.3). He offered extensive financial support for the modernization of the military in exchange for the PLA’s support and loyalty to the party. This initiated the structural elaboration of strong institutionalized Party-Army relations. Thus, when Deng yielded his chair of the CMC to the general secretary of the party, Jiang Zemin, a (new) actor was reestablished – the core. This was solidified when Jiang dismissed Yang Baibing as secretary general of the CMC and revoked the position altogether.

Hence, the reforms towards more open markets were a necessity to ensure the survival and legitimacy of the party – only with sustained economic growth could the party finance the military that would then in exchange support them. Therefore, one can say that by 1993, the interactions of the crisis were completed. The double morphogenesis resulted in the domination of the reformers as key corporate agents – including the triple morphogenesis of the actors: the institutionalization of the core by Jiang Zemin. The overall morphogenetic process ended in 1997. This is when, at the Fifteenth Party Congress, Deng’s compromise for army modernization in exchange for party loyalty was finally set into motion (Sommer, n.d.a). This means that the structures were adapted and changed and would from then on act as the new structural constraints on the actions of China’s corporate actors.